Dry soil conditions in the fall can be a blessing and a curse

By Shaun N. Casteel, Purdue Extension Soybean Specialist

Soybean harvest was one of the fastest on record with a pace that was about one week ahead of the 5-year average. Dry conditions cut seed fill short in late August to September; thereby, advancing the crop. These dry conditions continued through the fall allowing an early harvest based on calendar date and even the hour we could start combining.

Dry soil conditions during the fall can be a blessing and a curse. Soybean harvest certainly capitalized on early maturation and the extra hours (days and weeks) to bring the crop in. Unfortunately, grain moisture in many of the fields were down as low as 9 to 10 percent leading to a couple bushels of loss as the soybeans went across the elevator scales.

Soil sampling should have been turned around pretty quick – if the soil probes were able to get into the ground. The soil was dry and very hard in many fields. We need to proceed with caution on some of the early soil samplings if the soil was very dry. Or at least, we need to compare this year’s results with the previous sampling on the same fields.

In particular, soil potassium has a tendency to be lower when the soil is very dry at sampling. The potassium cation gets fixed or trapped in the interlayers of the 2:1 clays. Dry conditions can also limit potassium release from the crop residues. Soil pH values can be somewhat lower as well if spring applications of limestone did not have enough moisture for reactions to be fully realized.

In these situations, it is reasonable to compare soil test values of the past with the current ones – if sampled under dry conditions. Then to do some back of the envelope math for nutrient removal of the crops between the two soil samplings.

We are going to assume standard management practices for corn and soybean for the following nutrient uptake and removal rates. On average, corn removes 0.35 pounds of P2O5 and 0.25 pounds of K2O per bushel based on national averages. For example, a 220 bushel crop of corn would remove about 77 pounds of P2O5 and 55 pounds of K2O per acre (see Table 1).

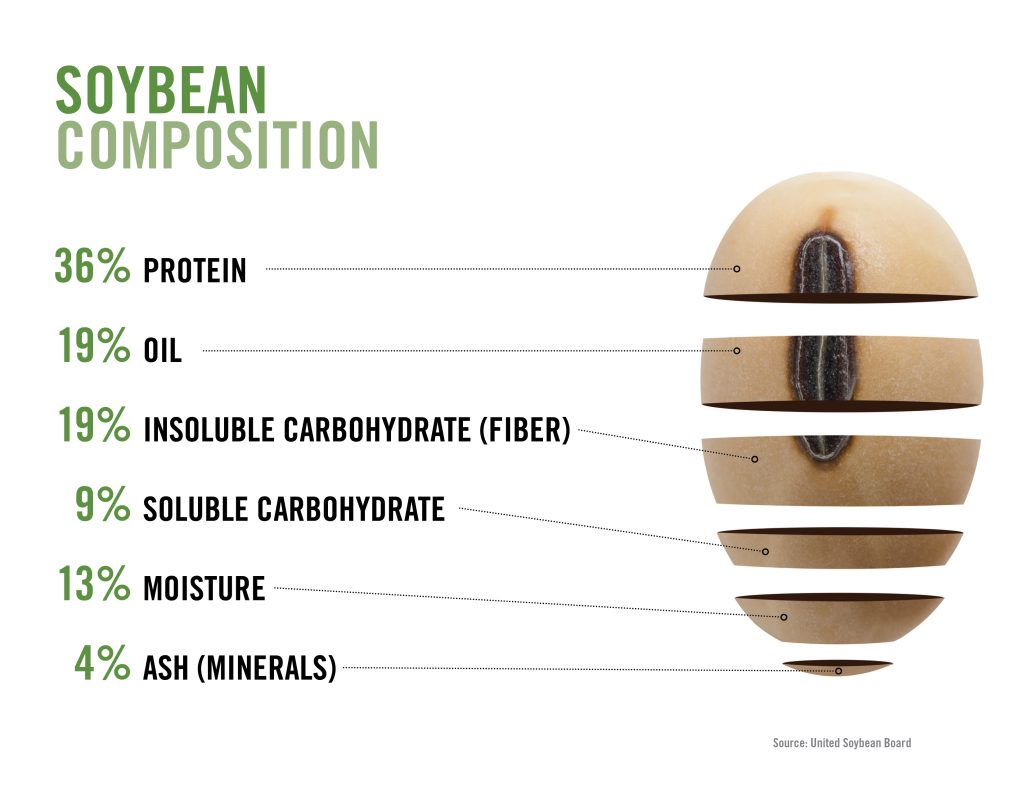

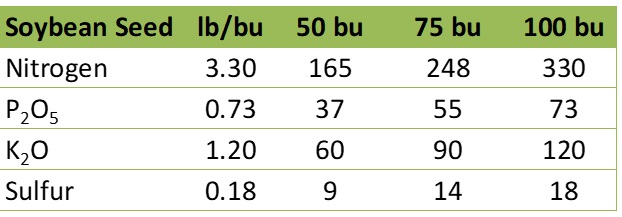

Soybean nutrient removals are available as well in Table 2. On average, soybean removes 0.73 lb P2O5 and 1.20 lb K2O per bu, so a 75-bu crop of soybean would remove about 55 lb of P2O5 and 90 lb of lb K2O per acre (Table 2). Obviously, fields have yield variations and those should be considered for both crops. I have also listed the grain removals of nitrogen and sulfur in Tables 1 and 2, but these are not to be used as replacement values.

Let’s assume that you produced 220 bushel corn in 2023 and 75 bushel soybeans in 2024. Grain removal would be about 145 pounds of K2O per acre (55 pounds from corn, 90 pounds of K2O from soybean). In an Iowa study, 10 pounds of K2O returned to the soil increased soil test 4 parts per million (8 pounds per acre).

If we back-calculate the potential change in soil test K, the soil sampled this fall should be approximately 58 ppm lower than the soil sampling two years ago when no potassium was added. Obviously, if fertilizer K was added between these samplings that should be offset in these calculations.

In the same Iowa study, 5 to 10 inches of rainfall released most of the potassium from soybean stover. Whereas, 10 to 15 inches of rainfall released about 50 percent of the potassium from corn stover.

In fact, 31 percent of potassium was still in corn stover after 20 inches of rain – a typical amount of rainfall for Indiana fall and winter. This should provide some guidance if the fall 2024 samplings were too dry and/or too early before the release of potassium from the crop residue.

Posted: November 16, 2024

Category: Indiana Corn and Soybean Post - November 2024, ISA, News, Purdue University, Sustainability